- New Chandra data of the supernova remnant G11.2-0.3 raise new questions about the timing of its origin.

- Previously, G11.2-0.3 was associated with an event recorded by Chinese observers in 386 CE.

- Chandra observations show that dense gas clouds lie along the line of sight between Earth and G11.2-0.3.

- This new information means that the supernova explosion would have been too faint to be seen with the naked eye from Earth.

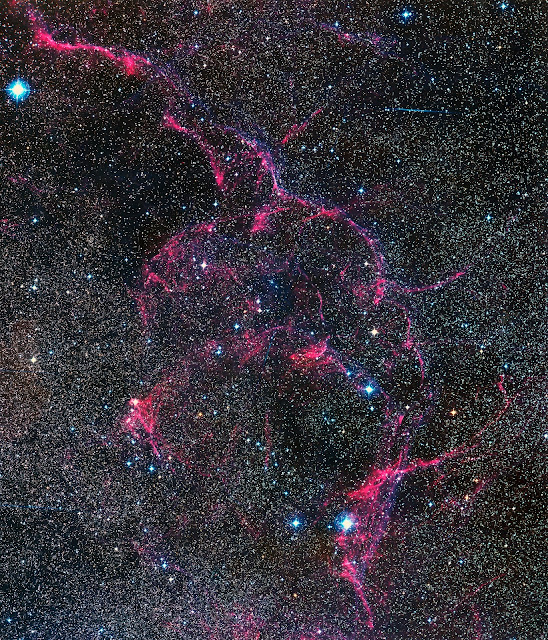

A new look at the debris from an exploded star in our galaxy has astronomers re-examining when the supernova actually happened. Recent observations of the supernova remnant called G11.2-0.3 with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory have stripped away its connection to an event recorded by the Chinese in 386 CE.

Historical supernovas and their remnants can be tied to both current astronomical observations as well as historical records of the event. Since it can be difficult to determine from present observations of their remnant exactly when a supernova occurred, historical supernovas provide important information on stellar timelines. Stellar debris can tell us a great deal about the nature of the exploded star, but the interpretation is much more straightforward given a known age.

New Chandra data on G11.2-0.3 show that dense clouds of gas lie along the line of sight from the supernova remnant to Earth. Infrared observations with the Palomar 5-meter Hale Telescope had previously indicated that parts of the remnant were heavily obscured by dust. This means that the supernova responsible for this object would simply have appeared too faint to be seen with the naked eye in 386 CE. This leaves the nature of the observed 386 CE event a mystery.

A new image of G11.2-0.3 is being released in conjunction with this week's workshop titled "Chandra Science for the Next Decade" being held in Cambridge, Massachusetts. While the workshop will focus on the innovative and exciting science Chandra can do in the next ten years, G11.2-0.3 is an example of how this "Great Observatory" helps us better understand the complex history of the Universe and the objects within it.

Taking advantage of Chandra's successful operations since its launch into space in 1999, astronomers were able to compare observations of G11.2-0.3 from 2000 to those taken in 2003 and more recently in 2013. This long baseline allowed scientists to measure how fast the remnant is expanding. Using this data to extrapolate backwards, they determined that the star that created G11.2-0.3 exploded between 1,400 and 2,400 years ago as seen from Earth.

Previous data from other observatories had shown this remnant is the product of a "core-collapse" supernova, one that is created from the collapse and explosion of a massive star. The revised timeframe for the explosion based on the recent Chandra data suggests that G11.2-0.3 is one of the youngest such supernovas in the Milky Way. The youngest, Cassiopeia A, also has an age determined from the expansion of its remnant, and like G11.2-0.3 was not seen at its estimated explosion date of 1680 CE due to dust obscuration. So far, the Crab nebula, the remnant of a supernova seen in 1054 CE, remains the only firmly identified historical remnant of a massive star explosion in our galaxy.

This latest image of G11.2-0.3 shows low-energy X-rays in red, the medium range in green, and the high-energy X-rays detected by Chandra in blue. The X-ray data have been overlaid on an optical field from the Digitized Sky Survey, showing stars in the foreground.

Although the Chandra image appears to show the remnant has a very circular, symmetrical shape, the details of the data indicate that the gas that the remnant is expanding into is uneven. Because of this, researchers propose that the exploded star had lost almost all of its outer regions, either in an asymmetric wind of gas blowing away from the star, or in an interaction with a companion star. They think the smaller star left behind would then have blown gas outwards at an even faster rate, sweeping up gas that was previously lost in the wind, forming the dense shell. The star would then have exploded, producing the G11.2-0.3 supernova remnant seen today.

The supernova explosion also produced a pulsar - a rapidly rotating neutron star - and a pulsar wind nebula, shown by the blue X-ray emission in the center of the remnant. The combination of the pulsar's rapid rotation and strong magnetic field generates an intense electromagnetic field that creates jets of matter and anti-matter moving away from the north and south poles of the pulsar, and an intense wind flowing out along its equator.

Image Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/NCSU/K.Borkowski et al; Optical: DSS

Explanation from: http://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2016/g11/